Scenario

You received a nice laptop from your company to work with, with excellent processing capabilities, a reasonable display and a good amount of RAM. The computer is supposed to be used for scientific research. You want to unleash all this power. However, the computer has two important limitations:

- Even though we are at the end of 2011, with many powerful Linux distributions available and even with Windows 8 on the horizon, someone decided that this otherwise excellent machine should instead run on the obsolete Windows XP.

- Due to policy issues, and not hardware or software limitations, it is not possible to partition the internal hard disk and install any other operating system for dual boot. The rationale stems from a single policy for all the departments.

There is no limitation on storing data, but there are also limitations on installing software to run in Windows. VirtualBox is explicitly blocked, as well as a number of other important applications.

A possible alternative to this hideous scenario could be run a Live CD of any recent Linux distribution. However, storing data between sessions in these live systems is complicated. Even more is to install additional software as needed.

Another possibility would be run the OS from an external drive. This works perfectly. However, for a laptop, to keep carrying the external disk all the time is cumbersome. Moreover, the disk takes a couple of seconds to be enabled again after a sleep or hibernation, so the system may not resume properly when trying to wake up.

A solution is as follows: create a large file in the NTFS partition, install Linux inside this file, and boot the system from an USB flash drive. To discourage curiosity, the file can be encrypted. This article describes the steps to accomplish this task using openSUSE, but a similar strategy should work with any recent distribution.

A solution is as follows: create a large file in the NTFS partition, install Linux inside this file, and boot the system from an USB flash drive. To discourage curiosity, the file can be encrypted. This article describes the steps to accomplish this task using openSUSE, but a similar strategy should work with any recent distribution.

Requirements

- A computer with an NTFS partition, inside which you want to have Linux, without tampering with the actual Windows installation.

- openSUSE installation DVD (tested with 12.1, and should work with other recent versions). Similar steps may work with other distributions.

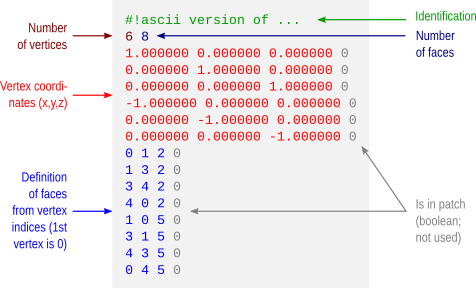

- A USB flash drive which will be used to boot the Linux system and will also store the kernel. This flash drive must stay connected during all the time in which the system is on, therefore it is more convenient if it is physically small. See a picture below.

- An external USB hard disk, to be used for a temporary installation that will be transferred to the file in the NTFS partition.

The procedure

Step 1: Plug the external hard disk and install openSUSE in it. Choose the desktop environment that suits you better (e.g. KDE/GNOME or other). It’s advisable to make this choice now, as it will save you time and effort, instead of leaving to add the graphical mode later. Leave /boot on its own partition as it will also facilitate steps later. Do not create a swap partition for this installation (ignore warnings that may appear because of this). Let’s call this as the system “E”, as it will reside temporarily on the External disk.

During the installation, install GRUB to the external disk itself, not to the internal drive (i.e., not /dev/sda), as you don’t want to tamper with the structure of internal hard drive or with the way as Windows boots. Before restarting the new system, if you changed the partitioning of the external disk, make sure that the partition that contains /boot has the “bootable” flag active (use fdisk to fix if needed).

Step 2: Make another install of openSUSE, this time to the flash drive. Again, put /boot on its own partition. Be generous with /boot, as it will accommodate 2 ramdisks and perhaps 2 or more kernels. Use at least 100MB. This installation can (and should) be the minimal, with no X (text-only). Let’s call this as system “F”, as it will reside in the USB Flash drive.

For a 16GB USB drive, a suggestion is:

- 1st partition: 14GB, FAT or similar, to use as a general USB drive, nothing special.

- 2nd partition: 1.8GB, ext4, to be mounted as as

/, and where the system will reside.

- 3rd partition: 0.2GB, ext4, to be mounted as

/boot.

During the installation:

- Like in the installation to the external hard disk, do not install GRUB to the internal drive, but to the USB memory stick.

- For the list of software, install the

ntfs-3g, ntfsprogs and cryptsetup. Install the man pages as well, as they may be useful.

Before booting the system F, make sure that the partition that contains /boot is bootable (use fdisk to fix if needed).

Step 3: Boot the system F, the flash drive. First task is to create the volume inside the NTFS filesystem, which will store the whole Linux system:

a) Create a key-file. No need for paranoia here, as the encryption is only to discourage any curious who sees these big files from Windows. Just a simple text file stored in the USB flash drive, separate from the encrypted volume:

echo SecretPassword | sha1sum > /root/key.txt

Note that in the command above, the password is not “SecretPassword”, but instead, the content of the file key.txt, as produced by the command sha1sum. This includes the space and dash (-) that are inside, as well as a newline character (invisible) at the end.

Do not store the keyfile in the NTFS partition. Put it, e.g., in the /root directory of the flash drive.

b) Mount the physical, internal hard drive that contains the NTFS partition:

mkdir -p /host

mount -t ntfs /dev/sda1 /host

c) Create a big file with random numbers in the NTFS partition. This will be the place where the full system will reside. For 100GB, use:

dd if=/dev/urandom of=/host/ntfsroot bs=2048 count=50000000

This will take several hours. You may want to leave it running overnight.

d) Mount it as a loop device:

losetup /dev/loop0 /host/ntfsroot

e) Initialize as a LUKS device:

cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/loop0 /root/key.txt

A message that any data on the device will irrevocably be deleted is shown. In this case, the device is the file full of random bits that we just created. So, confirm by typing ‘YES’ in capital letters.

f) Make a device-mapping:

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/loop0 root --key-file /root/key.txt

This will create a /dev/mapper/root device, which is an unencrypted view of the content of the big file previously created. The /dev/loop0 is an encrypted view and is not meaningful for reading/writing.

g) Create the file system that later will host the root (i.e., /):

mkfs.ext4 -b 1024 /dev/mapper/root

The block size will be 1024. Smaller sizes will mean more free disk space for a given amount of stored data.

h) Repeat the steps b-g for what will be the swap partition (8GB in this example):

dd if=/dev/urandom of=/host/ntfspage bs=2048 count=4000000

losetup /dev/loop1 /host/ntfspage

cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/loop1 /root/key.txt

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/loop1 swap --key-file /root/key.txt

mkswap /dev/mapper/swap

Step 4: [optional] Having made the initial configurations for the future / and swap, it’s now time to make a small modification of the initrd of the flash drive, so that it can boot from USB 3.0 if needed (even if the flash drive itself is 2.0, this step is still needed if you plan to plug it into an USB 3.0 port in the same computer):

a) Make a backup copy of the original initrd and update the symbolic link:

cd /boot

cp -p initrd-3.1.0-1.2-desktop initrd-3.1.0-1.2-opensuse

rm initrd

ln -s initrd-3.1.0-1.2-opensuse initrd

b) Edit the /etc/sysconfig/kernel and add the xhci-hcd module to the initial ramdisk:

INITRD_MODULES="xhci-hcd"

c) Run mkinitrd to create a new ramdisk.

cd /boot

mkinitrd

d) Rename it to something more representative:

mv /boot/initrd-3.1.0-1.2-desktop /boot/initrd-3.1.0-1.2-usbflash

The newly generated initrd will load the system that will be left in the flash drive, now with support for USB 3.0, and won’t be changed from now on.

Step 5: Restart the computer and boot into the system E (the external hard disk)

a) Edit the /etc/sysconfig/kernel and add these modules to the initial ramdisk:

INITRD_MODULES="xhci-hcd fuse loop dm-crypt aes cbc sha256"

Again, the xhci-hcd module is to allow booting the system from an USB 3.0 port (even if the flash drive is 2.0). If you don’t have USB 3.0 ports, this module can be omitted. The other modules are necessary to mount the NTFS partition, to mount files as a loopback devices, and to allow encryption/decryption using the respective algorithms and standards.

b) Run mkinitrd to create a new ramdisk.

cd /boot

mkinitrd

c) Make a copy of the newly created initrd to a place where it can be edited.

cp /boot/initrd-3.1.0-1.2-desktop /root/initrd-3.1.0-1.2-harddisk

mkdir /root/initrd-harddisk

cd /root/initrd-harddisk

cat ../initrd-3.1.0-1.2-harddisk | gunzip | cpio -id

d) Inside the initrd, edit the file boot/83-mount.sh (i.e. /root/initrd-harddisk/boot/83-mount.sh) and replace all its content by:

#!/bin/bash

# This will be the mountpoint of the NTFS partition

mkdir -p /host

# Mount the NTFS partition

ntfs-3g /dev/sda1 /host

# Mount the 100GB file as a loop device

losetup /dev/loop0 /host/ntfsroot

# Open the file for decryption (as a mapped device)

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/loop0 root --key-file /key.txt

# Mount the ext4 filesystem on it as /root

mount -o rw,acl,user_xattr -t ext4 /dev/mapper/root /root

# Mount the 8GB file as a loop device

losetup /dev/loop1 /host/ntfspage

# Open the file for decryption (as a mapped device)

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/loop1 swap --key-file /key.txt

e) Copy the losetup, cryptsetup, dmsetup and ntfs-3g executables to the initrd:

cp /sbin/losetup /sbin/cryptsetup /sbin/dmsetup /root/initrd-harddisk/sbin

cp /usr/bin/ntfs-3g /root/initrd-harddisk/bin

f) Copy also all the required libraries for these executables that may be missing (use ldd to discover which). There is certainly a way to script this, but to prepare and test the script will take as much time as to copy them manually. This has to be done just once.

g) Recreate the initrd:

cd /root/initrd-harddisk

find . | cpio -H newc -o | gzip -9 > ../initrd-3.1.0-1.2-harddisk

h) Copy the new initrd to the /boot partition of the USB flash drive, not to the /boot of the external hard disk. So, plug the USB drive and mount its boot partition:

mkdir -p /mnt/usbroot

mount -t ext4 /dev/sdX3 /mnt/usbboot

cp -p /root/initrd-3.1.0-1.2-harddisk /mnt/usbboot/

Step 6: Restart the system, now booting again into the system F (the USB flash drive):

a) Create two short scripts to mount and umount the encrypted filesystem. This will save time when you boot through the pendrive to do any maintenance on the installed system:

#!/bin/bash

mkdir -p /host

mount -t ntfs /dev/sda1 /host

losetup /dev/loop0 /host/ntfsroot

cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/loop0 root --key-file /root/key.txt

mkdir -p /mnt/ntfsroot

mount -t ext4 /dev/mapper/root /mnt/ntfsroot

#!/bin/bash

umount /mnt/ntfsroot

rmdir /mnt/ntfsroot

cryptsetup luksClose root

losetup -d /dev/loop0

umount /dev/sda1

rmdir /host

b) Execute the first, so that the file in the NTFS partition is mounted at /mnt/ntfsroot.

c) Mount the external disk partition that contains the / for the system E:

mkdir -p /mnt/hdroot

mount -t ext4 /dev/sdc2 /mnt/hdroot

d) Copy the whole system to the new location:

cp -rpv /mnt/hdroot/* /mnt/ntfsroot/

After this point, the external hard drive is no longer necessary. It can be unmounted and put aside.

e) Edit the /mnt/ntfsroot/etc/fstab to reflect the new changes:

/dev/mapper/swap swap swap defaults 0 0

/dev/mapper/root / ext4 acl,user_xattr 1 1

Step 7: Modify GRUB to load the appropriate initrd and load the respective system. Open the /boot/grub/menu.lst and make it look something like this:

default 0

timeout 8

title openSUSE 12.1 -- Hard Disk

root (hd0,2)

kernel /vmlinuz-3.1.0-1.2-desktop splash=silent quiet showopts vga=0x317

initrd /initrd-3.1.0-1.2-harddisk

title openSUSE 12.1 -- USB Flash Drive

root (hd0,2)

kernel /vmlinuz-3.1.0-1.2-desktop splash=silent quiet showopts vga=0x317

initrd /initrd-3.1.0-1.2-usbflash

title Windows XP

map (hd1) (hd0)

map (hd0) (hd1)

rootnoverify (hd1,0)

makeactive

chainloader +1

The only difference between the first and second entries is the initrd. In the first, the initrd will load the system that is inside the file in the NTFS partition, and which will contain the full graphical system. In the second, the initrd will load the simpler, text-only install on the USB flash drive.

Concluding remarks

We installed a modern, cutting edge Linux distribution inside a regular file in an NTFS partition. We did not modify any of the settings of Windows XP, neither did we partition the internal hard disk, nor tampered with the Windows registry or did anything that would violate any company rule. The boot loader, the kernel, and the initrd were left in an external device, the USB flash drive. When seen from Windows, only two inoffensive and unsuspicious files appear in the C:\. They contain the quiescent power of Linux.

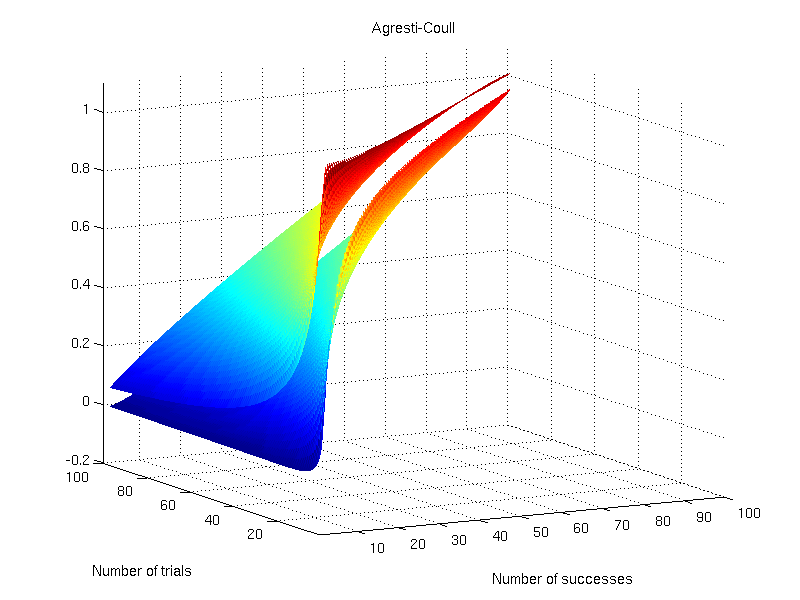

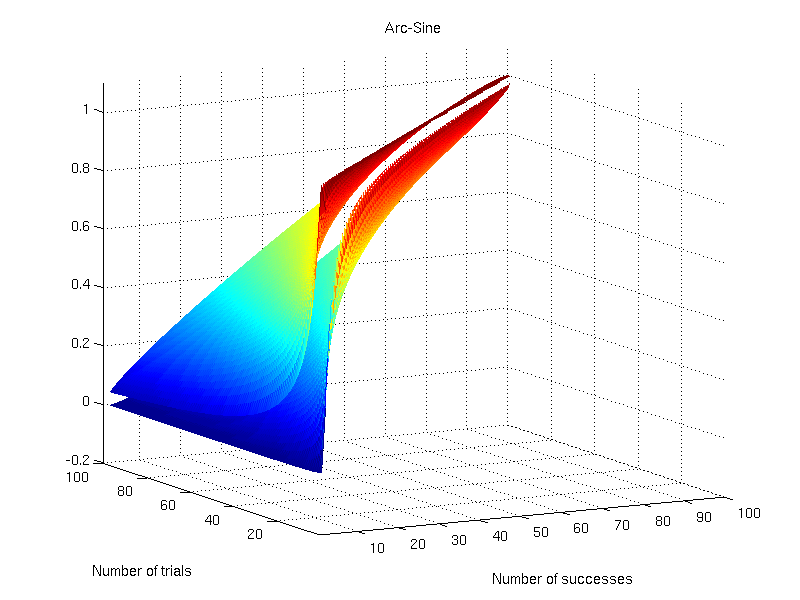

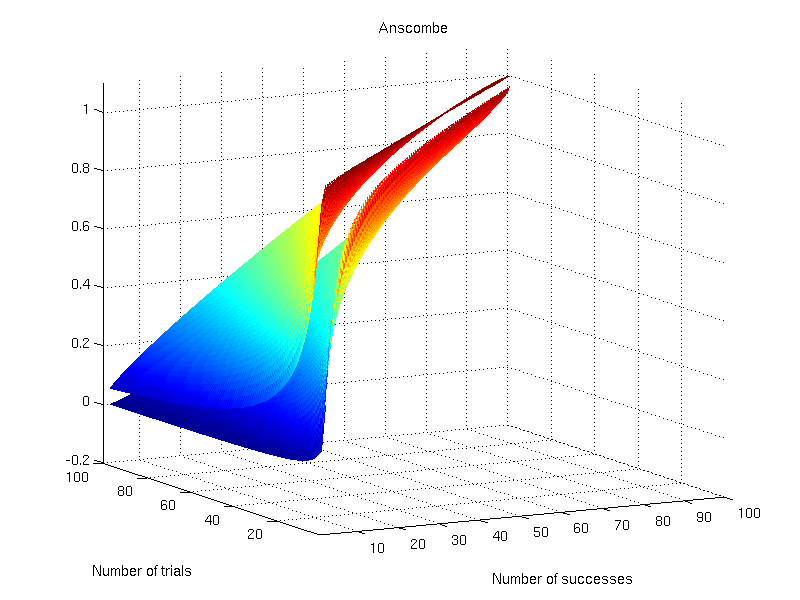

independent tests, each of these to test a certain null hypothesis

,

. For each test, a significance level

, i.e., a p-value, is obtained. All these p-values can be combined into a joint test whether there is a global effect, i.e., if a global null hypothesis

can be rejected.

is itself distributed in the

distribution with the appropriate number of degrees of freedom, may be made the basis of such a test. For in the particular case when

, the natural logarithm of the probability is equal to

. If therefore we take the natural logarithm of a probability, change its sign and double it, we have the equivalent value of

for 2 degrees of freedom. Any number of such values may be added together, to give a composite test, using the Table of

to examine the significance of the result. — Fisher, 1932.

. However,

is not uniformly distributed, even if the null is true for all partial tests, and cannot be used itself as the joint significance level for the global test. To remediate this fact, some interesting properties and relationships among distributions of random variables were exploited by Fisher and embodied in the succinct excerpt above. These properties are discussed below.

is the rate parameter, the only parameter of this distribution. The inverse cdf is, therefore, given by:

is a random variable uniformly distributed in the interval

, so is

, and it is immaterial to differ between them. As a consequence, the previous equation can be equivalently written as:

, which highlights the fact that the negative of the natural logarithm of a random variable distributed uniformly between 0 and 1 follows an exponential distribution with rate parameter

.

degrees of freedom, i.e.

, is given by:

, and solving the integral we have:

distribution with

is equivalent to an exponential distribution with rate parameter

.

is:

independent variables that follow each a

distribution is then given by:

distribution, however with degrees of freedom

.

into a p-value that is uniformly distributed when the global null is true? The product can be converted into a sum by taking the logarithm. And as shown above, the logarithm of uniformly distributed variables follows an exponential distribution with rate parameter

. Multiplication of each

by 2 changes the rate parameter to

and makes this distribution equivalent to a

distribution with degrees of freedom

. The sum of

of these logarithms also follow a

distribution, now with

degrees of freedom, i.e.,

.

following a

distribution, from which a p-value for the global hypothesis can be easily obtained.